Investors seem blind to Balfour’s value

That’s the stock market for you. Put UK companies in its big cement mixer and out can come some weird looking stuff. Take this for example: an outfit lucky enough to be turning business away whose core operations are valued at pretty much zip. How does that stack up?

It’s the riddle of Balfour Beatty: the construction outfit that looks built for these times but which, on a basic sum-of-the-parts valuation, may as well give up the day job. It has a market cap of £2.1 billion.

But you can get most of the way there simply by adding its £1.3 billion infrastructure investment portfolio to its average annual net cash of £700 million. Have investors missed its construction wing, forecast to have £9.6 billion sales this year?

True, after their experiences with Carillion and Interserve, some would sooner be nailed to the floor than invest in a construction group. But the Balfour boss, Leo Quinn, who took charge in 2015, has a near-ten year track record of proving he’s not about to vanish down a similar hole. And, even if construction is low margin — operating margins of 2.3 per cent in Britain and 1.1 per cent in America, on the latest half-year figures — work is piling up.

Quinn has focused Balfour on four key areas: the energy transition, transport and defence in the UK plus buildings in the US, everything from government offices to airports. And, with the Labour government “reinforcing commitments to critical national infrastructure”, as Quinn puts it, Balfour should not struggle to maintain its £16.6 billion order book. In fact, given what he calls a “capacity constrained” construction supply market, it can be “more selective” over the projects it does.

Labour came to power promising planning reform, decarbonised transport and a leg-up for defence spending to 2.5 per cent of GDP. Who knows if it’ll deliver on it. But, as Quinn notes, if it wants to see the “next industrial revolution” built on data centres and AI, “you’ve got to upgrade the electricity grid”, where National Grid is planning a £60 billion spend over five years. And, even if Labour misses its defence target, spending is going up.

All this plays into Balfour’s hands. Recent jobs include wiring all 116 T-pylons on the Hinkley Point C connection project for the grid; new transmission network contracts with SSE; and the Teesside power scheme, including a carbon capture plant, for BP. Notably, these are regulated or private jobs, not at the mercy of Treasury funding whims.

On defence, Balfour is Rolls-Royce’s construction partner for the expansion of its submarine site in Raynesway, Derby: a contract won off the back of the Aukus pact between the UK, US and Australia. And, on top of HS2, Quinn expects rail electrification work too.

Not screwing up contracts is a familiar challenge to construction groups. But, as Quinn puts it: “I don’t want to grow the top line because that’s a fool’s folly.” His focus is on profit and cash. And, even if the shares fell 2.5 per cent to 399.4p, underlying profit from operations rose 6 per cent last half to £101 million, with Balfour poised to return £160 million this year via dividends and buybacks. Lob in the £775 million handed back since 2021 and that’s almost half its market value. One day, investors may even spot that it’s something to build on.

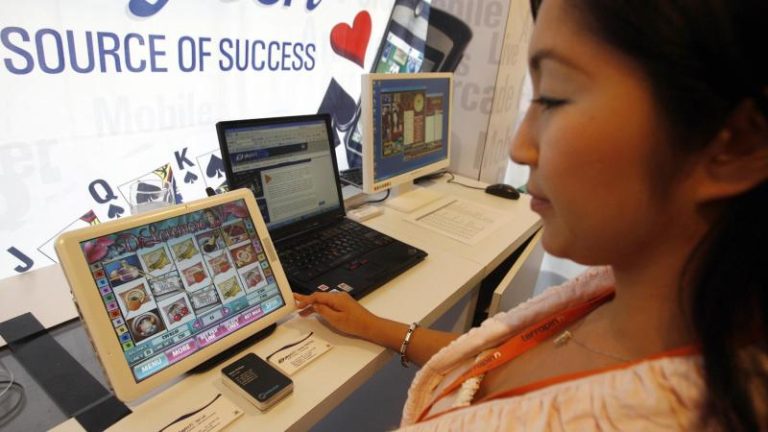

Place your bets

Some City bets take yonks to arrive. But, finally, the long-rumoured Playtech break-up could be happening. It’s been on the cards since Hong Kong investors, with about 40 per cent of the shares, teamed up in February 2022 to block a £2.1 billion agreed bid from Aussie outfit Aristocrat Leisure at 680p a share. The Playtech chairman, Brian Mattingley, didn’t even know who they were.

After that came the talk that to unlock a bit of value, Playtech could sell its Italian betting wing, Snaitech, so going back to its roots as the provider of software for gambling companies. In classic Playtech style, other stuff happened instead, such as its boss, Mor Weizer, bunking off to join up with another failed bid team before being ludicrously reinstated. Or the group having a legal dust-up with its biggest client, Mexico’s Caliente, in whose digital wing, Caliplay, Playtech has an economic interest of 49 per cent. That sort of joyous thing.

Still, at last Playtech investors are eyeing a jackpot: a bid for Snaitech, apparently worth £2 billion, from Flutter Entertainment, whose boss Peter Jackson, fresh from his US primary listing, is never far from an acquisition. The price is bigger than Playtech’s £1.9 billion market value — even after the shares shot up 14 per cent to 612p. It’s also a decent return on the €846 million Playtech paid for Snaitech in 2018.

True, it’s not a done deal. Flutter already owns Italian betting group Sisal, bought for £1.62 billion in 2021. So, it could face competition issues, even if a deal would only see it leapfrog Italian No 1 Lottomatica, which last year bought SKS365 for €639 million.

But at least Playtech’s esoteric Asian investors won’t get a vote on this deal. How lucky is that?

Dog’s breakfast

Not everyone is a fan of the Mars Bar-Pringles sandwich: chocolate caramel goo plonked between two slices of sour cream and onion-flavoured cardboard. But you’d think investors in the US-listed Kellanova are getting a taste for it, with Mars paying $36 billion for a range also including Pop-Tarts and the relatively healthy Special K.

As a family business, Mars need not care what people think of the price, its waistline or the lack of fruit and veg in its diet. So, given its plans to “develop a sustainable snacking business that is fit for the future”, Pringles looks an obvious buy. They also go extremely well with another Mars brand: Pedigree Chum.